Inequality and economic recession

Who suffers the most in society when an economic recession hits?

Please enter a keyword and click the arrow to search the site

Or explore one of the areas below

The research findings of Paolo Surico, Professor of Economics at London Business School, have challenged schools of thought — including the role played by inequality in the overall economy. This has been intensely debated in academic literature, but his research shows that income disparity actually amplifies the effects of a recession.

Paolo's research has helped shape the macroeconomic policies of European governments, and crystalised the role played by inequality in the aggregate economy.

His paper on Consumer Spending and Property Taxes underpinned a policy decision by the Italian government to abolish a much-hated property levy on primary residences in 2016. The long-running tax, known as IMU, was restored in 2011 by then-Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti, who wanted to shore up the public finances during the eurozone debt crisis.

The levy raised billions of euros in annual revenue for state coffers, but it created problems too. It led to large spending cuts among households with mortgages or lower income, according to Paolo’s research, co-authored with Riccardo Trezzi, formerly of the Federal Reserve Board.

The study found that higher tax rates on second homes had a minimal impact on consumption, as these typically wealthy homeowners drew on their savings. Paolo concluded that removing the levy on main dwellings would stimulate consumption, as households could use the money they otherwise gave away in taxes. At the same time, keeping the tax on second homes would keep money flowing into state coffers.

These findings directly influenced the decision of Italy’s next premier, Matteo Renzi, to scrap the tax on primary residences from 2016, demonstrating the application of Paolo’s ideas, and his engagement with policymakers.

Paolo’s recent research details how, when interest rates increase and the economy cools, households that drive the majority of spending are the ones which tend to see the largest drop in their income. So there is a “second-round” effect of monetary policy in which it reduces consumption and income, but particularly among households with mortgage debt or less wealth.

This proves that inequality can deepen in an economic downturn — food for thought as policymakers around the world seek to soften the impact of high inflation and interest rates.

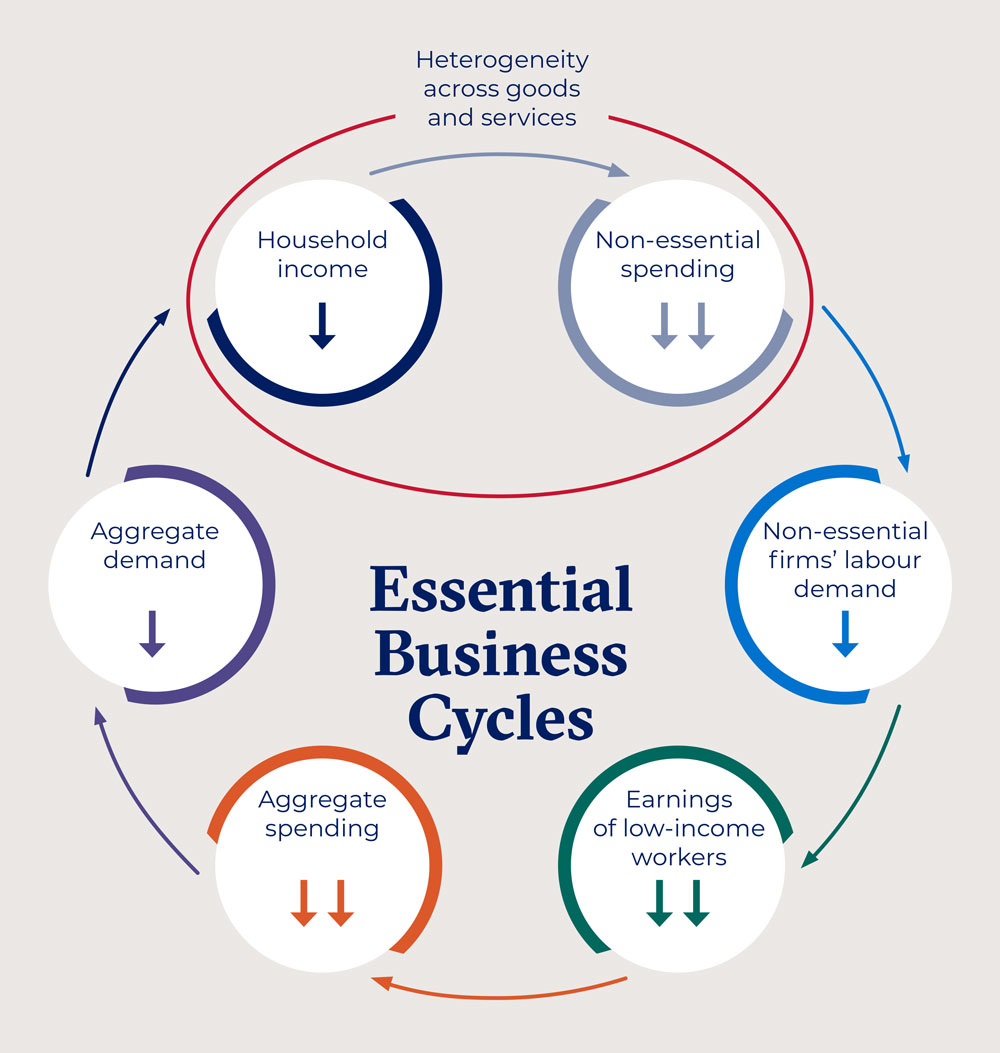

The pandemic highlighted another second-round effect of monetary policy. Paolo’s paper examining the topic showed how the reduction in spending following rate increases is concentrated in sectors which employ a disproportionately large number of low-income workers.

As demand for services like hospitality and entertainment slows, these workers face redundancy or reduced wages, further weakening consumption. So, the tightening of monetary policy is a double-whammy for the working classes. And this, says Paolo, implies that income inequality has a negative impact on the aggregate economy. This research was co-authored with Michelle Andreolli (a former LBS student now at Boston College) and Natalie Rickard (an LBS PhD student).

Through his work, he hopes to identify the individuals, firms and categories of spending that drive most of the changes in productivity, wages, employment and consumption — changes caused by economic policies. Those insights can help maximise the impact of such interventions. Such insights are badly needed in the UK in particular, for a variety of reasons.

Compared to other G7 nations, Britain has faced an especially weak recovery. Inflationary pressures have lingered in the UK for longer than elsewhere, forcing the Bank of England to squeeze further and the government to pursue a tight fiscal policy.

This has resulted in a further hit to household incomes and there is clearly a need for policy change to tackle the UK’s fundamental problems, including feeble productivity, weak business investment, and the damage to trade caused by Brexit.

Indeed, Paolo argues that most of the policies enacted by governments and central banks around the world seek to stabilize the whole economy, whereas much less is known about how the consequences of these policies are distributed across society.

The overarching theme of Paolo’s research is that the consumption of households with specific economic traits, or the investment of firms with particular financial characteristics, often determine the fortunes of another set of companies, thereby impacting their demand for capital and labour. This sets off a cascade of second-round effects that have the potential to generate a significant impact on overall productivity, income and living standards.

Paolo points to how fiscal policy drives changes in consumption. When governments cut personal income taxes, a burst of consumer spending follows, but this effect is short-lived. In comparison, cuts to corporation tax have only a marginal impact on gross domestic product (GDP) in the short-run, but the effect is amplified over time. The research on this was co-authored by Joseba Martinez, who is an Assistant Professor of Economics at London Business School

Firms in some sectors, he says, will use part of the excess capital to invest in R&D, which fosters productivity and boosts output, as his research proves. But it depends on the sector; manufacturing companies are more likely to invest their windfall into R&D, but firms providing services tend to return the cash to shareholders via dividends. These findings imply that switching from a broad to a more targeted fiscal approach would help unlock long term growth in the economy.

More widely, his research shows how powerful R&D can be in stimulating economic growth. In his paper with LBS PhD student Juan Antolin-Diaz , soon to be published in the American Economic Review, Paolo looks at 125 years of U.S. quarterly data to examine the effects of government spending on productivity and economic growth. The paper finds any shift of government spending towards R&D drives innovation, which in turn drives productivity growth.

This effect is often associated with wars, due to increased military spending, that in turn lifts innovation and private sector investment, as companies race to develop new technologies to support the war effort. Later on, in peacetime, that technology is often adapted for use in the private sector, leading to a significant uptick in long-term productivity. A good example of this is how DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in the US) created the digital protocols that underpin the modern internet.

However, it is the fostering of innovation that is important here -wars are not special in this regard - and indeed, the paper finds that there are several examples in American economic history that have been characterised by a significant shift in public spending towards R&D at times in which no war occurred. So the UK could raise its own dismal productivity, even in peacetime, by spending more on R&D to seed the innovations that would eventually work their way into the private sector, increasing the effectiveness of worker effort, says Paolo.

All major economies suffered a productivity slump in the wake of the financial crisis, but the UK’s slowdown has been especially acute. Since 2007, productivity — the value of output per hour worked — has averaged just 0.3%.

Ultimately, Paolo’s research resonates with policymakers and highlights how his findings can be applied to everyday life and help to address societal needs, particularly for those more likely to feel the impact from economic downturns.

Most of the policies enacted by governments and central banks around the world seek to stabilize the whole economy, whereas much less is known about how the consequences of these policies are distributed across society.

Paolo Surico

Our research is helping to solve some of society's most challenging questions and concerns.

Our faculty publish over 100 papers and articles every year, many of which are featured in top-ranked business journals. Discover what our researchers are working on and how they are shaping the world.

The study reveals that the motherhood penalty, characterised by reduced earnings opportunities in wage employment due to motherhood status, significantly drives female entrepreneurship, particularly among women facing wage discrimination, offering insights into women's career choices amidst workplace inequality.

LBS faculty: Olenka Kacperczyk

The research shows that judgments of hypocrisy are biased by social motivations, with people more likely to accuse enemies and defend allies based on how they perceive similarities in behaviour.

LBS faculty: Jonathan Berman

Research combining mathematical modelling with data from executive hiring, crowdfunding, and patent applications challenges the assumption that increasing the number of women in application pools will improve gender diversity.

LBS faculty: Isabel Fernandez-Mateo