Discover fresh perspectives and research insights from LBS

Think at London Business School: fresh ideas and opinions from LBS faculty and other experts direct to your inbox

Sign upPlease enter a keyword and click the arrow to search the site

Or explore one of the areas below

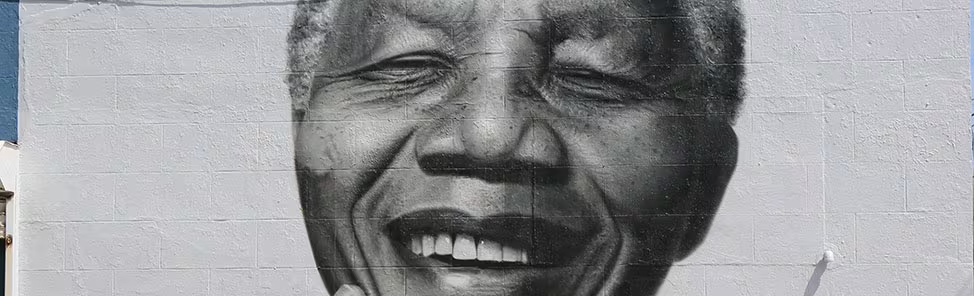

The late South African president exemplified a level of self-mastery that all business leaders should aspire to, says Nigel Nicholson

The most important battles that any leader has to face are resolved in that mysterious mental space we call the self. Nelson Mandela is the most memorable and revered leader in modern history for his actions. It was his inner strength that powered his historic achievements.

This was underscored for me recently when I talked with two people in South Africa who had known him well: Mandela’s lifelong friend but political opponent Mangosuthu Buthelezi and Christo Brand, his prison guard leader for the last 15 years of his incarceration. There are lessons for us all.

Mandela was a man of iron-self-discipline, unshakeable vision and values, enormous human warmth, high intelligence and an articulate tongue. He adhered to strict ethical and strategic boundaries, yet he knew when to be flexible and meet the enemy with a smile – even an embrace. He is rightly judged to have been a very special leader. But how did he get to be that way?

Leadership is demonstrated in moments. Mandela’s example shows how it shines through when the person is confronted with a situation – a problem, a person, an opportunity – that the leader grasps and uses. Sometimes this may be with deliberation and thoughtfulness and sometimes it will be based on instinct, but in either case, it yields powerful results. The key to this is what psychologists call self-regulation.

This quality was visible in Mandela’s power in and out of prison. He was the natural and unchallenged leader of political prisoners on Robben Island, as Brand told me on the boat back from the infamous prison. When Brand pitched up on Robben Island, Brand was a naïve, mild-mannered and politically ignorant 18 year-old. He scarcely knew who these top security prisoners were. He was greeted with stately courtesy by a tall lean 60-year-old black man who addressed him graciously as “Mr Brand”, spoke fluently in Afrikaans and immediately established a rapport with his captors.

Even the older political prisoners accepted Mandela’s natural authority. Brand recalls how Mandela enjoined them to maintain mental and physical discipline, getting them to follow his example of self-improvement through voracious study. He insisted that “We are not criminals but political prisoners and we must respect the guards as men doing their job and not make life difficult for them.”

This is the same moral clarity that gave his nation the truth and reconciliation process, thereby avoiding a vengeful bloodbath. Brand maintained contact with Mandela after he had become President and wrote a wonderful homage to his hero in the book, “Mandela: My Prisoner, My Friend.”

I also spent some hours interviewing Mangosuthu Buthelezi, a Zulu prince and one of Mandela’s fellow freedom-fighters. Despite a political rift that sparked something close to civil war between the largely Zulu followers of Buthelezi’s Inkatha Party and Mandela’s ANC, the two remained friends to the end. Buthelezi recalls a late meeting shortly before Mandela’s death where they reminisced, and talked about their life journeys.

Think at London Business School: fresh ideas and opinions from LBS faculty and other experts direct to your inbox

Sign up